Quick facts

Find quick answers to questions you might have about cystinosis.

There are three clinically recognised forms of cystinosis, depending on the age of presentation and degree of renal disease severity:1–3

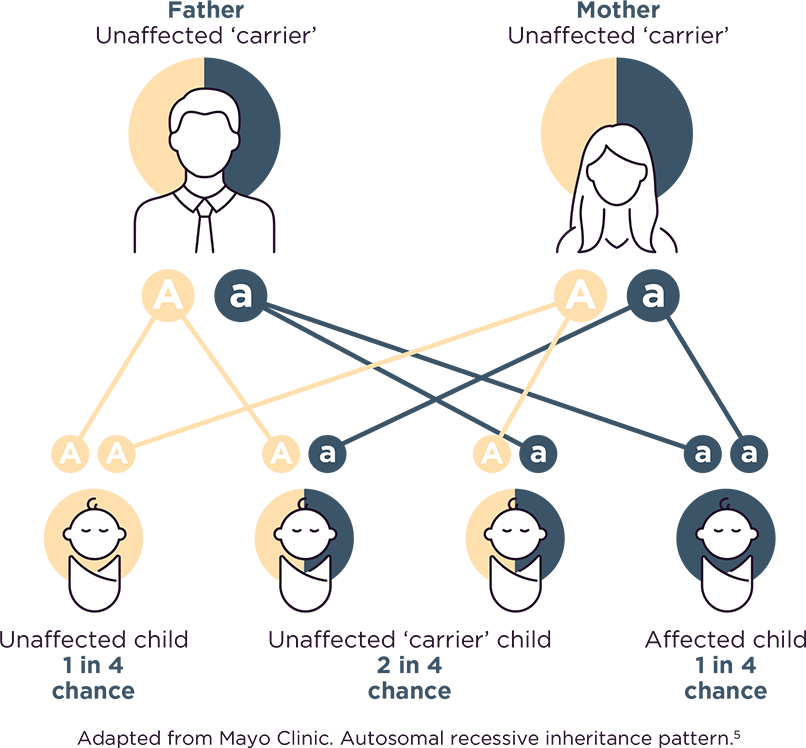

In people with cystinosis, cystine (an amino acid) builds up in the body’s cells and the cells are unable to remove it. Cystinosis is an inherited disease that is passed from parent to child, when an abnormality in the CTNS gene leads to problems with the way cystine is stored in the body. Cystinosis can only develop in children who receive a non-working copy of the cystinosis gene from each parent.1

There are three types of cystinosis, which are classified according to how severely the kidneys are affected and at what age the symptoms start appearing; infantile nephropathic cystinosis (the most common form), juvenile or late-onset cystinosis and adult/ocular cystinosis.1

Because nephropathic cystinosis affects every cell in the body, its symptoms are very broad and diverse. Although the kidneys are affected first, almost every organ in the body is at risk of damage.2

Patients with nephropathic cystinosis appear normal at birth, but within the first year of life they often present signs that suggest their kidneys are not working as well as they should. Patients may also have impaired growth, loss of appetite or rickets.2

For full information on the symptoms of cystinosis through different stages of life, visit the Symptoms page.

Cystinosis is an inherited disease that is passed from parent to child, when a gene (CTNS gene) that doesn’t work the way it should leads to problems with the way cystine is stored in the body.1

Cystinosis can only develop in children who receive a non-working copy of the cystinosis gene from each parent.3,4 For each pregnancy where both parents are unaffected carriers:

• There is a 1 in 4 chance that both parents will pass along a nonworking copy of the gene and the child will have the disorder.3,4

• There is a 2 in 4 chance that one parent will pass on the gene change and the other won't, meaning the child will be a carrier for the disorder, but not have it.3,4

• There is a 1 in 4 chance that both parents will pass along a working copy of the gene and the child will not have the disorder and will not be a carrier.3,4

Cystinosis is an ultra-rare disease that affects fewer than 2 people in every million.2

Cystinosis can be diagnosed using a test that looks at the levels of cystine in the white blood cells.1 This is usually carried out in an expert centre by a kidney specialist (paediatric nephrologist) or metabolic specialist.2 A slit-lamp examination may also be carried out by an ophthalmologist to look for eye crystals which appear by 1–2 years of age.2 If available, genetic testing for gene mutations can also be carried out by a geneticist to confirm the diagnosis and characterise the specific mutation a patient has.1

At 6 to 12 months, symptoms of cystinosis include: Fanconi syndrome, excessive urine production (polyuria), excessive thirst (polydipsia), dehydration, loss of electrolytes in urine, glucose present in urine (glucosuria) and normal blood glucose levels, amino acids present in urine (aminoaciduria), growth retardation and rickets.1,2

At 1 to 2 years, symptoms include cystine crystals present in the eye (corneal crystal accumulation).1

At 3 to 4 years, symptoms include sensitivity to light (photophobia).1

Successful management of this condition requires a wide range of treatments. Primarily, this is cystine-depletion therapy, which works by reducing cystine levels in cells throughout the body. Cystine-depletion therapy is given both orally and topically (as eyedrops). Kidney transplantation may be required, which needs to be followed by treatment which dampens the immune system. Other treatments may include insulin to treat diabetes and thyroxine to replace missing thyroid hormones.2,6,7